Paco Cemetery, in the living memory of many, was where students hung around while skipping classes, where the marijuanas were smoked, where you smoked cigarettes because you were hiding from your parents, where lovers made out and many more. It was known only to the local people and the faces you would have seen in there were your neighbors, usually no more than 25 years old. There was a fireman across the street who was also a manunuli, and every summer, boys went there to say goodbye to their foreskins. It was on the curbside of Paco Cemetery that I last saw Ramon, that Spanish man who used to angrily talk in front of the store owned by a Chinese on the corner of San Jorge and Sison. Whatever it was he was mad about, I had no idea because his words were all in Spanish. Last time I saw him, he was manning a makeshift store with a native woman just a few feet from the entrance of Paco Cemetery. I asked him if his name was Ramon (first and last time I talked to him). He didn't say a word, just a nod and a smile. But that was my memory, and I have always wondered about the memory of those who went there while in its surrounding there were rice paddies, nipa huts and factories made of wood.

“In Paco, the motionless body of a boy and his entrails disappear from his mother; to a woman in love, the object of her affection; to a loving husband, the irreplaceable wife; to a loving son, his loved and venerated parents” — Recuerdos de Filipinas. Cosas, casos y usos de aquellas ... v.2. por Francisco Cañamaque Published 1877-79

“July 17

At five in the morning, the insurgents began attacking our line of defense, followed by small interruptions all day. Some unpleasant incidents happened. In the chapel of Paco Cemetery, while there were people reciting their prayers for the dead, a bullet penetrated the enclosure, naturally producing an alarm. A projectile from the insurgents’ cannon broke the wheels of one of our gun carriages in Tondo. In return our artillerymen broke into pieces the enemies’ cannon.” — El sitio de Manila (1898) Memorias de un voluntario.

By: Juan Toral Published: 1898

“Its defect is that it is very near the capital” —Cuentos filipinos, por Don José Montero y Vidal.

Published: 1883

“It was four in the afternoon, October 3, 1879, 37° centigrade (98°F), and two hundred and plus dead according to the funeral statistics of the week. Majority of this was caused by a fever. I don’t know what the doctors call it, nor do I care. However, I will call it thermometric fever because I have observed a house where a doctor was using a thermomether, and the number of living people went down. One less piece of marble in the shops of Rodoreda and one more page in the triennial register of Paco.

In the neighborhood of my respectable Sr. D. Francisco, the rent of any of the rooms within the three floors requires three years’ worth of advanced payment. If after three years the lease is not renewed, there will be an eviction by pickaxe, without anyone’s right to complain, given that the landlord, through the publication in the Gaceta, has the generosity to grant a deadline of twenty days

Why would a cemetery be called Paco? This is the question they have never been able to answer.” — De Manila à Albay, por Don Juan Álvarez Guerra. Published 1887

“Padre Fonseca says that it is calculated that about P20,000 were spent by the Dominican Corporation on charity and public welfare during the great calamity. Aside from the monetary aid, every one who belonged to the religious order provided very relevant services that when the epidemic ended, the Governor, the provincial deputy, the illustrious Ecclesiastical Council of Manila and the Ayuntamiento, personally thanked the religious order in the name of the city and wanting to perpetuate the memory of the sacrifices made for those who were affected by cholera, spontaneously gave a special pantheon to the Dominicans in the new Paco Cemetery with the following inscription:

Divi religiosis Dominici sua beneficia recordatus Hocce gratítudinis monumentum Manilae dicavit Senatus” — Sobre una "Reseña histórica de Filipinas." : Colección de artículos Published 1906

“The Ayuntamiento of Manila, recognizing their many services and not knowing how to pay them back, donated to the Daughters of Charity the perpetual usufruct of a section of nine niches in Paco cemetery. The visitors can still see this section in the ancient necropolis of the city of Manila.”— Los padres paules y las hijas de la caridad en Filipinas; breve reseña histórica de la labor realizada en estas islas por la doble familia de San Vicente de Paul, 1862-1912, por un sacerdote de la congregación de la misión.

“Baron Honoré Fréderic Adhemar Bourgeois du Marais , a Frenchman of noble birth and noble sentiments , was the son of Viscount Bourgeois du Marais. He was buried in Paco Cemetery.” —-The Philippine Islands; a political, geographical, ethnographical, social and commercial history of the Philippine Archipelago, embracing the whole period of Spanish rule, with an account of the succeeding American insular government, by John Foreman, F.R.G.S. Published 1906

In the Paco Cemetery in Manila, and elsewhere in the islands, it is not unusual for relatives or friends to keep fresh flowers on the graves of the dead for a number of years.—- A handbook of the Philippines, by Hamilton M. Wright; with three new maps, made especially for the book, and one hundred and fifty illustrations from photographs. 1908

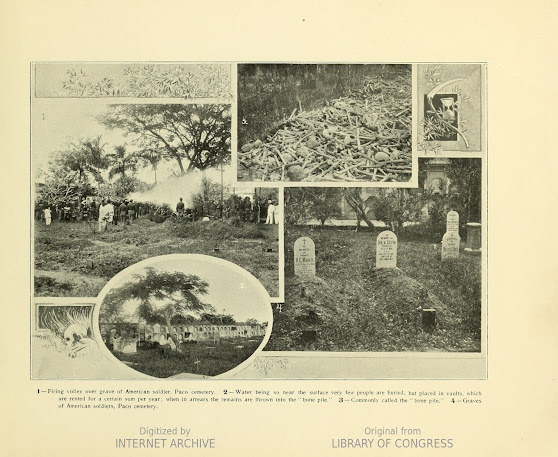

“One of the peculiarities to be noticed by the visitor is the recent dates exhibited on the slabs of the different vaults . Although the cemetery is nearly one hundred years old , as a rule none of these inscriptions shows an age greater than five or ten years . This will readily be understood when one learns that a system of rental exists , and if the rent is not paid when due , evictment follows . Until a few years ago this practice was made very evident by the display of bones thrown about in an inclosure at the back of the cemetery , where they found a final resting place . “ — Manila, the pearl of the Orient; guide book to the intending visitor, Published 1908

“The run takes one through an interesting part of the city . Paco Cemetery is passed , and after leaving the borders of town the line runs through paddy fields and rural scenes until Santa Ana is reached .” —-Manila, the pearl of the Orient; guide book to the intending visitor, by: Daniel O’Connell 1908